Some books tell us stories which enchant us, filling us with wonder. Others, while enchanting us, remind us of the things that are truly important to us. And then there are those few which teach us a bit about story and why stories–and storytelling–matter.

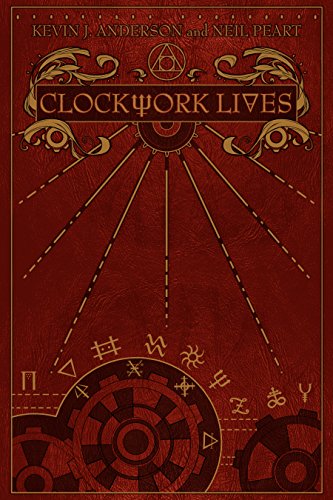

Kevin J. Anderson and Neil Peart’s Clockwork Lives is such a book. For while it is, in some ways, unlike any book I had ever read, it is also, in many ways, a book about every book I had ever (or have ever) read. It is a book about the stories we tell ourselves–and the stories that tell us about ourselves.

In this new twist on the Canterbury Tales, Anderson and Peart give us, instead of a group of pilgrims telling tales as they travel to pay homage to the “holy blissful martyr,” they leave us with just one, Marinda Peake. This wallflower of a young woman is not on a religious quest, but a personal one. As per her father’s bequest, she must travel the world and interact with others so she can fill a blank book with their stories. And only after the book has been filled can she claim return home to claim her inheritance.

To collect these stories, she need not write anything, merely find men and women willing to offer a drop of their blood. And when that drop touches the alchemically treated pages of a book her inventor father had crafted, their stories will tell themselves. The very paper will bring out the essence of each individual’s tale, the essence of his life. Or hers.

This “magical” book thus tells perhaps a truer story than one we might tell ourselves. As she gathers the tales, Marinda finds that while some people’s stories require little more than a line or two, others are more epic, filling pages upon pages.

And slowly, Miranda comes out of her shell, becoming increasingly bolder in approaching others. Through story, she comes to better understand the world around her as she connects more readily with those who have had life experiences different from her own.

When she, for example, secures a drop of blood from “The Seeker,” Cabeza de Vaca, a renowned explorer who has supposedly discovered the Seven Cities of Gold, she learns that he has discovered nothing but the ability to entertain. His tall tales are just that. Though he has found no legendary lost cities, he has learned how to talk as if he had. “I didn’t consider what I was doing lying,” he says through the drop of his blood. “I was entertaining. I was inspiring. And if I could give these lackluster people a sense of wonder for the mere price of a tankard of ale–or two or three–then it was a good thing by far.”

Isn’t a sense of wonder what we are all looking for when we listen to a tale, read a book, or watch a movie?

Marinda’s travels give her something greater than just this sense of wonder at the power of story. And we the readers see it, delight in it, and appreciate it. We wonder as well, why some people are better storytellers while others have lives that make for better stories.

Not only does this book enchant us, but it also makes us think about story—and its meaning.

One more thing. Toward the end, Marinda learns that “for a story to serve its purpose, it had to be shared.” Stories, in short, help us connect to our fellow human beings.

Stories must be shared.

As should this book.