Every now and again, someone gives you the gift of a word. It can be a friend saying something in conversation, a bit of dialogue in a movie, or even the title of a book. And when you find the meaning behind that word, in the context of the conversation, the story of the film, or the argument of the book, it helps you better understand your own life—and your passions.

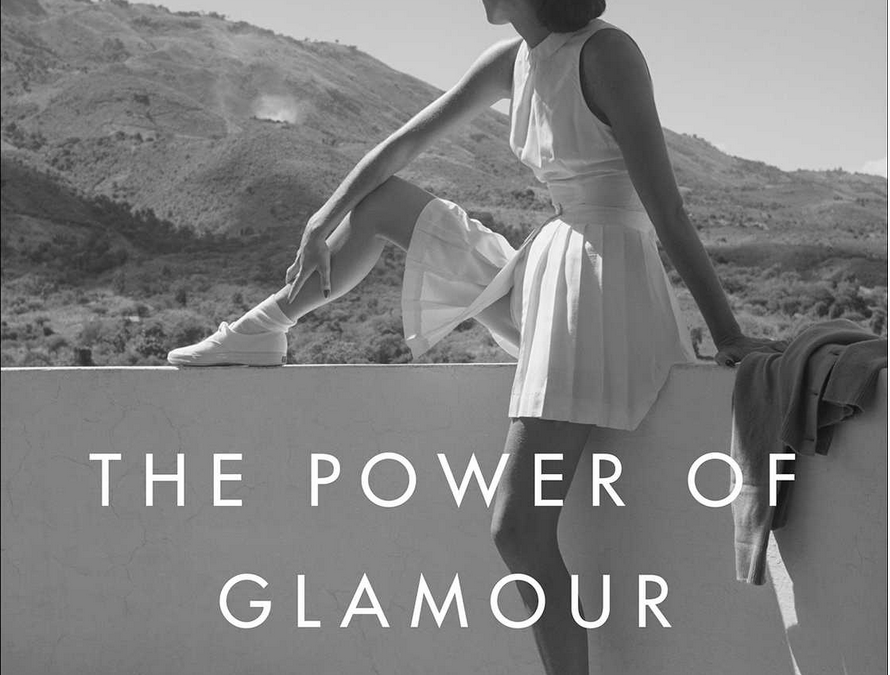

I had just such an experience five years ago when I read Virginia Postrel’s The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion. I might not have bought (and then read) the book had I not enjoyed Virginia’s very rational essays on (mostly) unglamorous topics. You see, I had once thought glamour referred mostly to beautiful women with stylish hairdos and clad in well-designed dresses. A glamorous women become a icon of feminine beauty, drawing the eyes of all, the men who desire her, the women who envy her, and others of both sexes just enchanted by the figure she cuts.

I thought of Helen of Troy in Book Three of The Iliad where the legendary beauty Helen arrives on the ramparts of Troy to watch the contest between Menelaus and Paris, the two men vying for her. Catching sight of her, “the old chiefs” of that ancient city, as Robert Fagles translates, understood why men “under arms” could “suffer years of agony… for such a woman.”

As I read The Power of Glamour, however, I learned that Helen was not the only glamorous figure in The Iliad. Achilles too had his own glamour. “Homer’s fiction,” Postrel writes, “lay in idealizing his hero.” Alexander the Great, she continues, would “project his own yearnings onto the glamorous figure of Achilles.” And Julius Cæsar in turn would project his onto Alexander.

Glamour, she explains, “elicits a distinctive emotional response… a sense of projection and longing.” It is not reality. It is rather an illusion, an idealized image.

We see these two characteristics—illusion and subjective response—playing out in one of the phenomenon’s oldest forms: martial glamour. From Achilles, David, and Alexander through knights, samurai, admirals, and airmen, warriors have been icons of masculine glamour, exemplifying courage, prowess, and patriotic significance. Beginning in the nineteenth century, warfare was one of the first contexts in which English speakers used the term glamour in its modern metaphorical sense.

And indeed, I chanced upon that idea (if chance it was) in a 1934 book, Romance & Legend of Chivalry. In the Preface, A.R. Hope Moncrieff tells us that his “volume deals with the days of old when knighthood was in flower and gallant gentlemen in armor fought the Saracen and rescued damsels from false caitiffs.” The time was the Middle Ages—and the place, Western Europe. Some of the tales “circle about historic events, and elaborate actual incidents into glamorous romance” (emphasis added).

Knights in shining armor. The Middle Ages. Glamorous romance.

Were not then the legends of King Arthur glamorous tales? Is not The Lord of the Rings a glamorous epic?

Each presents an idealized image of a medieval world. They left out all the struggles of day-to-day life, frequent diseases, shorter lifespans, gruesome deaths on the battlefield. (Postrel reminds us that “glamor’s second essential element: grace” involves “the actual or apparent elimination of flaws, distractions, weaknesses, costs….”)

Instead of showing us the gritty reality and the dirty details, the Arthurian tales and Tolkien’s epic present an ideal, giving us something to aspire to. They elicit an emotional response.

A Tolkien geek since I was twelve, I realized that I had been enchanted by medieval glamour for the better part of my life. A book which I had (at first thought) was about the appeal of stylish women in beautiful dresses helped me better understand a lifelong passion for a world that never was–and likely could never be.

This book helped me realized that I had never really wanted to live in the Middle Ages. I just aspired to be like the heroes–and wizards–who inhabited an idealized version of them.